The mirror’s regret: Iraqi women reverse the synthetic beauty era

Shafaq News

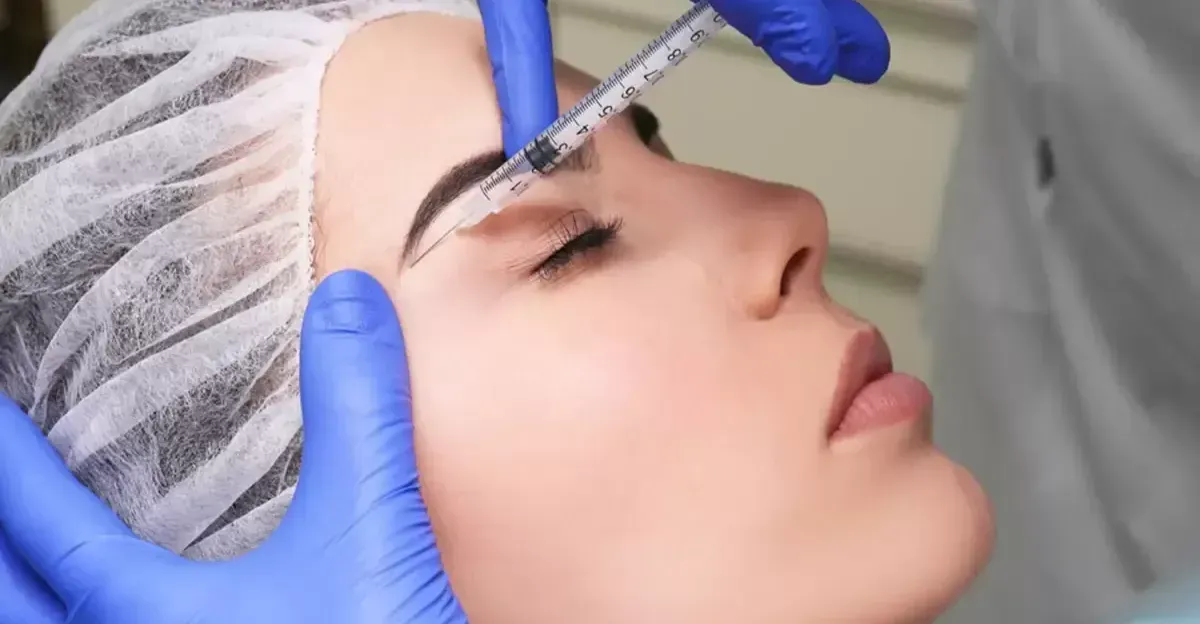

Sarah Muzhir did not walk into the cosmetic clinic this time to enhance her face. She went in hoping to recover it. In her twenties, Sarah had spent years moving between clinics, encouraged by advertisements and social media posts promising beauty, confidence, and self-improvement. Each visit ended the same way: another injection, another “adjustment,” another promise that this would be the last.

“No one ever talked about consequences,” she recalled to Shafaq News. “Only about what needed fixing next.”

What began as a minor cosmetic enhancement slowly turned into a cycle. Her features softened, then blurred. The face she saw in the mirror no longer felt like her own. Youthful contours gave way to swelling and imbalance. Over time, all traces of her natural features —the beauty of youth and individuality— faded away.

This time, Sarah chose to dissolve the fillers altogether. She wanted to return to her natural appearance. “I wasn’t trying to look better anymore, I was just trying to look like myself again.”

She also began exploring less invasive treatments to address sagging, though the emotional toll lingered. The regret for entering clinics she never truly needed weighed heavily.

Undoing the Artifice

Two sisters, Tiba and Rusul, are among those trying to undo the damage.

“My face became grotesquely swollen after years of injections,” Tiba told Shafaq News. “I couldn’t tell my face from my sister’s, or from other girls’. We all started to look the same.”

For Rusul, the moment of realization came in public spaces. “You walk into a mall or a restaurant and see your face repeated again and again. That was painful,” she added.

Both sisters pointed to aggressive online marketing and discounted cosmetic packages as the trigger. “The offers were tempting. No one warned us where this could lead,” Rusul recalled.

Some clinics even promoted filler removal with slogans like “by yourself, not copy,” signaling a growing niche for women seeking to undo previous procedures.

The Digital Mirage

For generations, beauty standards in Iraq valued natural features, modesty, and personal character. Cosmetic procedures were rare, and appearance was not expected to override social values or identity.

That balance has shifted sharply over the past two decades. Social media platforms now define attractiveness through filtered, edited, and surgically enhanced images. Influencers and celebrities promote sculpted cheekbones, full lips, and sharply contoured faces as benchmarks of success and desirability.

The pressure to conform has been relentless. Many young women compare themselves to digital images that are neither natural nor attainable, internalizing the belief that cosmetic intervention is necessary to be accepted, admired, or chosen. This pressure extends beyond appearance, influencing self-worth, social standing, and even marriage prospects — turning beauty into a competitive, standardized currency.

Read more: New rules for beauty: Iraq tightens regulations for cosmetic procedures

Inside the Mirror

Speaking to Shafaq News, cosmetic specialist Shaimaa Al-Kamali attributed the filler boom to deeper psychological vulnerabilities. “Beauty begins with mental health,” she noted, pointing out that “What we are seeing is not a lack of beauty, but a lack of self-acceptance.”

Al-Kamali explained that many women seek cosmetic procedures without having any real physical flaw. Instead, they arrive carrying internalized dissatisfaction fueled by comparison and unrealistic expectations, a vulnerability some clinics exploit for profit.

She described her professional stance: although she has worked in cosmetic medicine since 2016, she has performed filler injections in only three cases, all strictly cosmetic, and refuses lip fillers or facial overfilling. “I always advocate for preserving the natural youth of the skin without altering features.”

Repeated filler injections stretch the skin and create dependency on increasingly larger volumes, eventually leading to “overfilling,” a stage where facial harmony is lost. While fillers can be dissolved, the process is neither simple nor guaranteed.

“Removal does not restore the face automatically,” she warned, recommending collagen-stimulating treatments as a safer alternative, which offer natural firmness and radiance without altering the face.

Profit over Person

Behind many of these stories lies a cosmetic industry that expanded rapidly and unevenly after 2003.

As demand surged, hundreds of cosmetic centers opened across Iraq, many operated by unqualified individuals —beauticians, salon owners, or non-specialists performing invasive procedures without proper oversight. Health officials later acknowledged that only about 105 cosmetic centers nationwide are officially licensed, while hundreds operate illegally, particularly in Baghdad.

In recent months, the Ministry of Health launched inspection campaigns, shutting down more than 100 centers and banning dentists from performing cosmetic injections such as fillers and Botox.

Parliamentary committees have intervened following complaints about unlicensed staff administering procedures, while medical authorities have warned that the commercial misuse of the term “cosmetic” blurred the line between medical treatment and beauty services, exposing women to serious health risks.

The backlash against fillers is not confined to Iraq. Internationally, public figures have begun speaking openly about reversing cosmetic procedures. US model Blac Chyna has warned followers that fillers do not enhance identity but gradually erase it.

In Iraq, this global shift coincides with a local awakening shaped by regret, physical harm, and growing rejection of standardized beauty.

For Sarah, dissolving fillers marked more than a cosmetic decision. It was an attempt to reclaim ownership over her face. “I believed beauty was something I had to inject. Now I understand it was something I already had.”

Read more: Self-acceptance vs. idealized images: Beauty in modern Iraq

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.