Stateless in their homeland: The unending exile of Iraq’s Feyli Kurds

Shafaq News/ In the quiet alleys of eastern Baghdad, Amira Abdul-Amir Ali moves through her days under the weight of silence. Her footsteps echo with decades of exclusion—an exile not from geography, but from legal existence.

Born in 1960 and raised in Iraq, she remains, at 64, a citizen of nowhere. No official record affirms her Iraqi identity. Her life is suspended in a bureaucratic void—without recognition, rights, or recourse.

Amira’s story mirrors that of tens of thousands of Feyli Kurds, a

Shiite Kurdish minority deeply woven into Iraq’s social and economic fabric.

For generations, they ran businesses, held public posts, and called Iraq home.

But shifting political tides erased that belonging.

Displacement by Decree

The persecution of the Feyli Kurds was deliberate and protracted. In the early 1970s, the Baath regime under President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr initiated mass deportations, accusing Feylis of “Iranian allegiance.” Under Saddam Hussein, the campaign intensified, peaking in 1980 with one of Iraq’s most egregious state-led displacements.

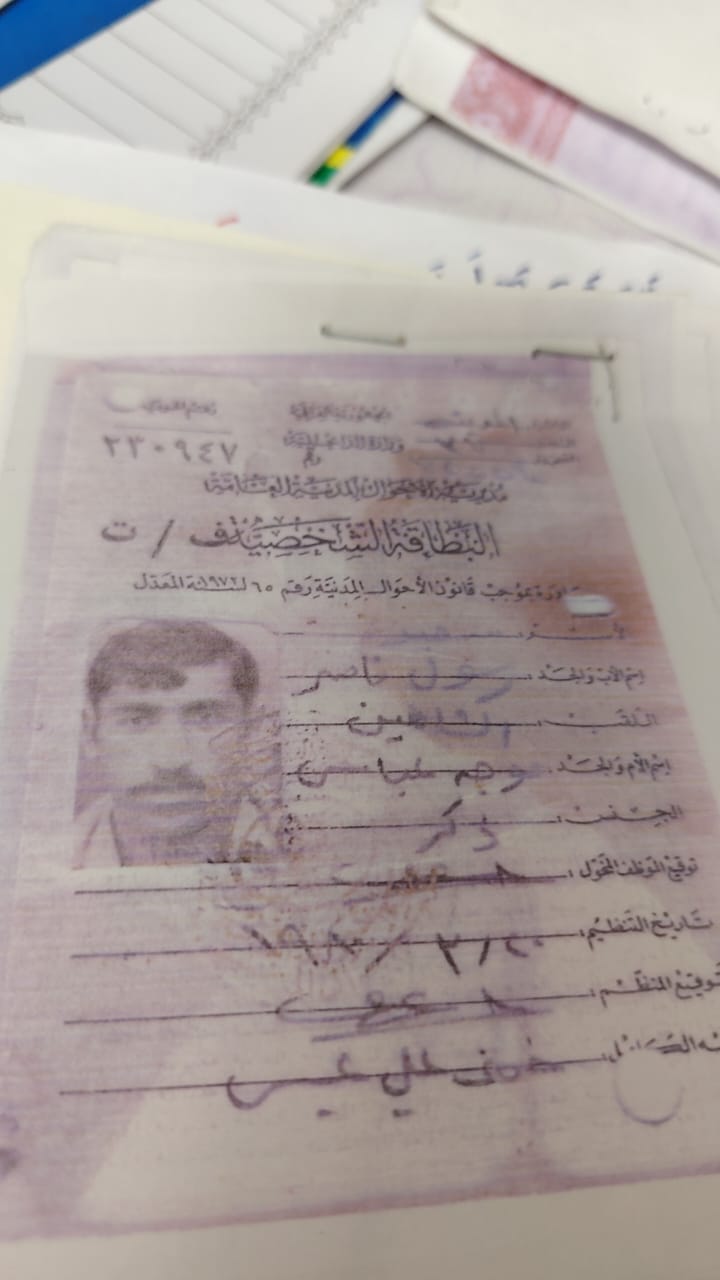

Citizenship papers vanished overnight. Families were rounded up and forced into Iran. Homes, shops, and savings were confiscated. Over 500,000 Feyli Kurds were expelled, according to estimates. Thousands of young men disappeared, likely executed or buried in unmarked graves. Baghdad’s Feyli professionals and merchants were among the hardest hit.

The Iraqi Ministry of Human Rights reports that more than 1.3 million people went missing nationwide between 1980 and 1990. Feyli Kurds bore a disproportionate share of that toll.

Recognition Without Relief

In 2010, Iraq’s High Criminal Court classified the deportations and disappearances as genocide. A year later, Parliament echoed that recognition. Yet these acknowledgments, while historic, brought little in practice.

Pledges to restore citizenship, return property, and compensate

victims remain largely unfulfilled. Many survivors returned to Iraq after the

2003 fall of Saddam Hussein—hopeful, but soon entangled in a labyrinth of

paperwork. Reinstating citizenship required documents lost during exile or

raids, and the state offered scant support in recovering them.

A Name Without a Nation

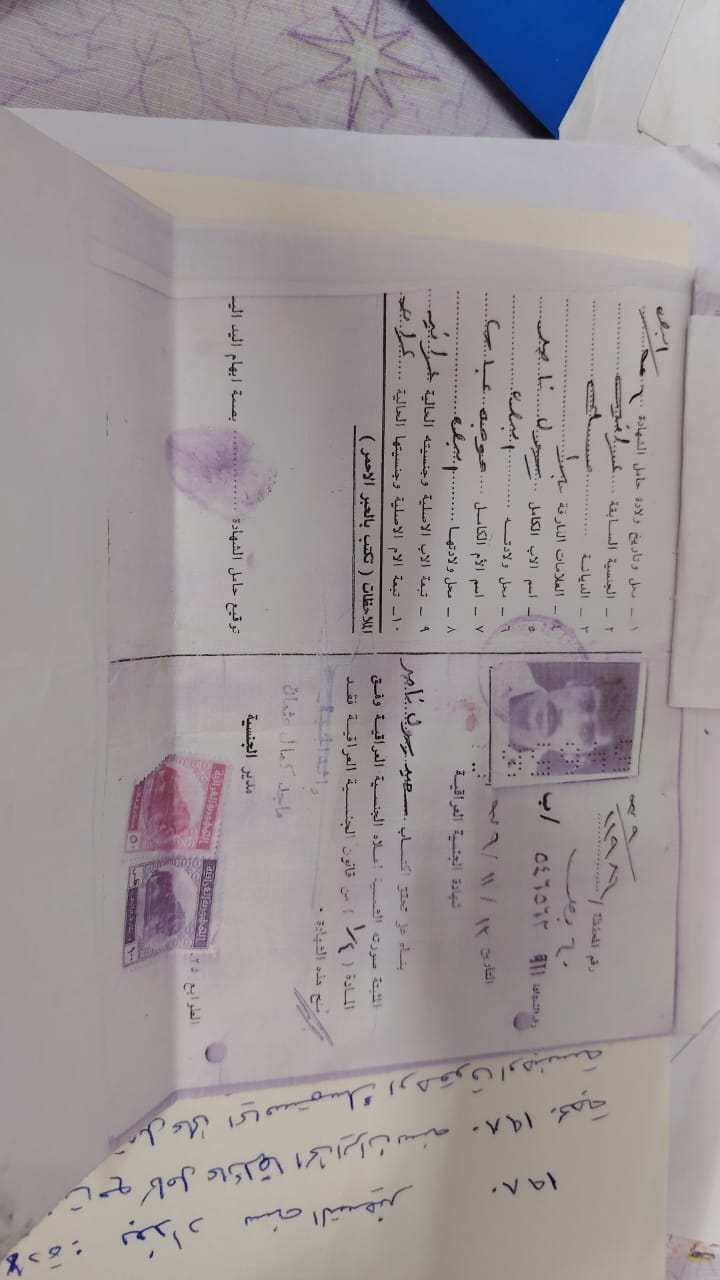

Amira’s life exemplifies this bureaucratic limbo. Deported with her family in 1980, she spent decades in Iran. There, she married an Iraqi prisoner of war in a religious ceremony—valid by custom, but unregistered by Iraqi authorities.

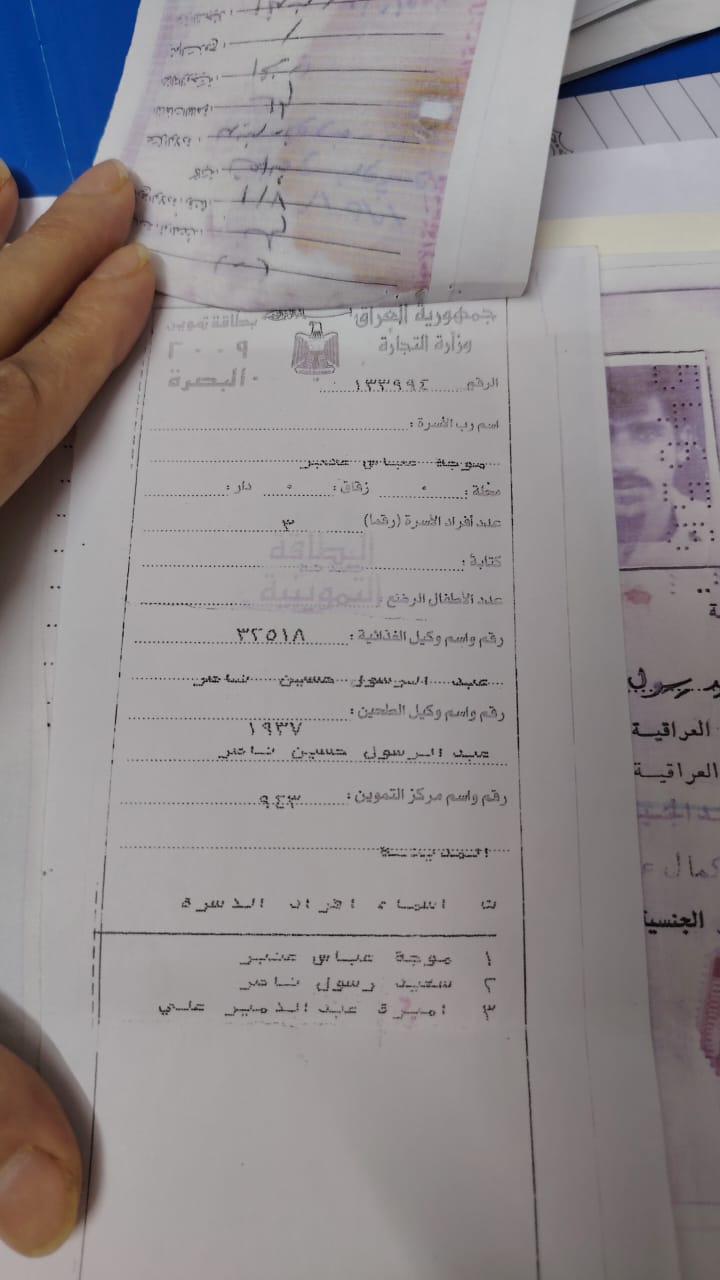

After returning to Iraq post-2003, her husband failed to submit her nationality paperwork. When he died, Amira was left alone, legally invisible. She holds no national ID, cannot access public healthcare or education, and is excluded from Iraq’s food ration system.

“All I ask is to be treated like everyone else,” she told Shafaq News. “To restore just a piece of my lost dignity.”

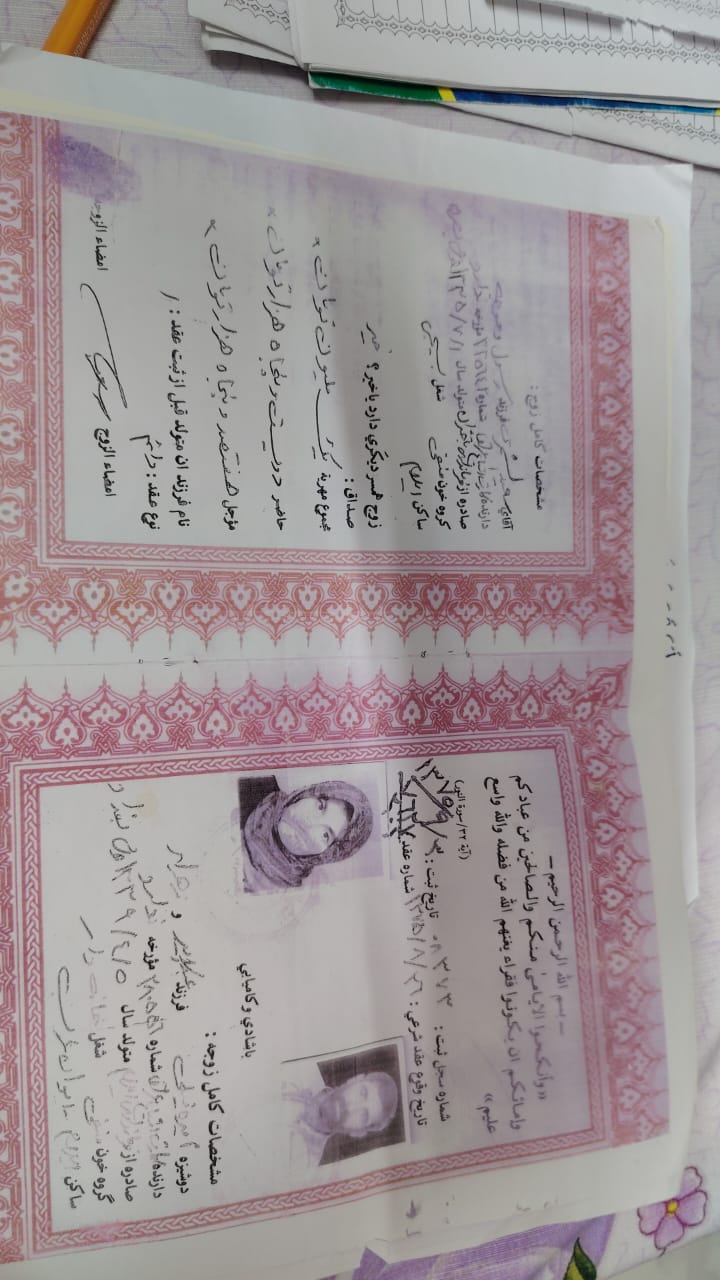

Her entire legal identity today fits in a worn file folder—an

unregistered marriage contract, a few aging residency papers—none sufficient to

restore her rights.

Bureaucracy and Gender

Iraqi law allows reinstatement of Feyli citizenship in principle, but implementation is sluggish and inconsistent. For women, the hurdles are even greater. Iraq’s civil registry system still leans heavily on male guardianship. Without a husband or male relative to file her case, Amira has effectively vanished from official records.

Her experience reveals how gender compounds legal exclusion. Years in exile, outdated rules, and systemic corruption create a maze most cannot navigate. Her case is just one of hundreds stuck in this legal paralysis.

Human Rights Watch has noted that Iraq’s transitional justice

efforts are undermined by fragmented politics and selective enforcement. Legal

structures exist, but urgency and willpower are lacking.

Genocide as Daily Reality

The 2010 genocide ruling was a milestone—but more than a decade later, material justice remains absent. Property has not been restored. Compensation has not reached most victims. And citizenship remains elusive for many.

Some Feyli Kurds have reintegrated. But others—like Amira—live in legal shadows. For them, “genocide” is not merely a past crime—it is a daily condition.

“I live as though I have no right to anything… no home, no document, no voice,” Amira said. “Orphaned by both parents—I just want to be treated as an Iraqi. That’s all.”

A Humanitarian Path Forward

Amira continues to appeal to Iraqi leaders—especially Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani and Interior Minister Abdul-Amir al-Shammari—seeking a humanitarian solution. Iraqi law does include provisions for exceptional cases, particularly involving mixed marriages and displaced persons, but they are rarely and inconsistently applied.

Human rights advocates stress the need for urgent administrative reform: simplify application procedures, recognize informal marriages in exile, and allow women to reclaim citizenship without male intermediaries.

The United Nations defines legal identity as a foundational right—one that enables access to education, healthcare, political participation, and economic life. Without it, individuals are effectively erased from public existence.

For Amira and many others, restoring that identity is not just a matter of paperwork. It is a reclamation of belonging, dignity, and home.