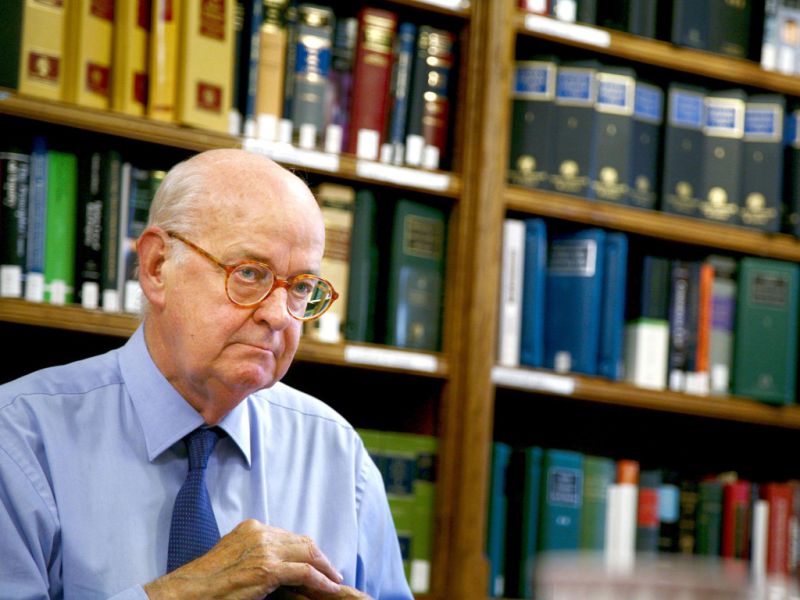

Lord Steyn: Judge who opposed Tony Blair and George Bush over Iraq war and Guantanamo

Law lord Johan Steyn was a principled champion of basic human rights, free speech, democracy and the rule of law, and his liberal and often outspoken views angered many, not least the Blair and Bush administrations following the Iraq War and its aftermath.

His outspokenness resulted in the Blair Government breaking with precedent to block his appointment to a House of Lords’ judicial committee. It was the first time that a government had ever sought, and obtained, an alteration in the composition of this judicial committee.

During his 10 years as a law lord, Steyn never opened his mouth in the chamber of the House of Lords, believing that judges should play no part in Parliament. However, throughout his years on the bench, his strongly held views made themselves heard, but only through his court judgments, lectures to lawyers and fellow judges, and articles in academic journals.

He was also a leading advocate of the principle that judges should not defer to Parliament and politicians simply because politicians are accountable to the electorate. Judges too have a duty to the public, he argued, and should not simply take ministers’ word for it, but should probe and seek evidence.

In November 2003, Steyn, a native Afrikaner, made headlines as a serving judge when the international media picked up a lecture to colleagues in which he branded Guantanamo Bay “a monstrous failure of justice, which is a hellhole of utter lawlessness”. He said that America’s trial by military tribunal amounted to “a kangaroo court which makes a mockery of justice”. His card was marked by the British Government.

Steyn then publicly attacked Lord Hoffmann, a fellow law lord and Afrikaner, for suggesting that the courts should not interfere with certain government decisions. “In troubled times,” he noted, “there is an ever-present danger of the seductive but misconceived judicial mindset that ‘after all, we are on the same side as the government’.” This, he added, was a “slippery slope, which tends to sap the will of judges to face up to a government guilty of abuse of power”.

Two years earlier, when Britain introduced executive detention without trial, Steyn had responded by delivering another scathing lecture to the judiciary. He expressed the view that the UK opt-out from the European convention on human rights, which the Government had to do to bring in the legislation, was “not justified”.

To the dismay of many, having already criticised the then-Home Secretary, David Blunkett, of using “weasel words” in justifying his policy on asylum seekers, Steyn found himself removed, at Blunkett’s insistence, from the panel of law lords (led by Lord Bingham of Cornhill) to decide on the legality of detaining foreign terror suspects without trial.

He retired as a judge in 2005, and became chair of the human rights group Justice. In that role, he dismissed Tony Bair’s rebuttal of critics who claimed the Iraq war had made London a more dangerous place as “a fairytale”.

After the 7/7 bombings, Blair heralded new anti-terror legislation saying “the rules of the game are changing”. Steyn insisted: “Maintenance of the rule of law is not a game. It is about access to justice, fundamental human rights and democratic values.”

Few judges were prepared to be so critical or vocal. But in 2006 Steyn launched a blistering attack on the criminal justice system and foreign policy under Blair. He said: “Absolute power encourages authoritarianism which is a creeping phenomenon ... Our government has been prone to it.”

Steyn condemned New Labour for its assault on human rights, declaring himself to be “deeply sceptical” of a national identity card scheme, saying he shared comedian Rowan Atkinson’s fears that the new religious hatred legislation will criminalise satire.

Steyn also criticised the “flood” of criminal justice legislation, most of which were “half-baked ideas adopted in haste” and later shelved. Like Lord Alexander of Weedon, he considered that the Iraq War was unlawful agreed that “in its search for a justification in law for war, the government was driven to scrape the bottom of the legal barrel”.

Born in Cape Town, South Africa, in 1932, Johan van Zyl Steyn was the son of an eminent law professor at Stellenbosch and the grandson of one of the founders of the Transvaal province. He grew up a bookish child and after attending the Jan van Riebeeck School, began his law studies at the University of Stellenbosch before being awarded a Rhodes scholarship to read English at University College, Oxford. It was there that he met his first wife Jean Pollard with whom he had two sons and two daughters, who survive him: Martin, Deon, Linda and Karen.

He was called to the bar in South Africa in 1958 and appointed senior counsel (equivalent to QC) of the South African Supreme Court in 1970. It is perhaps his experience of having lived under apartheid that he sought to fight for the rule of law and human rights – the West was by no means immune to despotism, in his view. Perhaps he saw himself at the coalface of maintaining democracy’s core pillars intact.

One of few whites who spoke out against apartheid, he later wrote of his time: “It was a period of institutionalised tyranny and cruelty in the richest country in Africa, inflicting great suffering on millions of black people. The Government, by and large, could and did achieve its oppressive purposes by a scrupulous observance of legality.”

So incensed by the regime, in 1973 Steyn abandoned his seat on the Supreme Court and emigrated to the UK to start again on the bottom rung of the legal ladder. The South African Prime Minister, BJ Vorster, was said to have been furious.

Steyn joined the prestigious Essex Court Chambers in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London, practising as an international commercial lawyer for 12 years. He made a remarkable rise in judicial ranks, given English was not his first language and took silk in 1979. Despite disparaging comments in some quarters because of his strong accent and ponderous delivery, he was admired for his clear arguments, his skill in cross-examination and his uncanny knack of knowing how and when to plant a seed of thought in a judge’s mind.

In 1977 he married his second wife, Susan Lewis, who survives him along with his stepson and stepdaughter.

Steyn was appointed a High Court judge in 1985 thanks to the Lord Chancellor, Lord Hailsham, and then promoted to Lord Justice of Appeal and sworn of the Privy Council in 1992. He became a Law Lord in 1995.

Three years later, he was one of the judges who ruled by a 3-2 majority that the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet was not entitled to claim sovereign immunity from prosecution and should be extradited to Spain to face trial for his crimes. Steyn argued that defending Pinochet’s immunity from prosecution would effectively mean that the Nazi’s “final solution” to exterminate the Jews was lawful. However, the judgment was set aside after the revelation of Lord Hoffmann’s ties to one of the parties to the hearing, Amnesty International, though it was partially reconfirmed in 1999. The following year, Pinochet was released on medical grounds by the Home Secretary Jack Straw.

A 2002 lecture, Steyn accused Lord Irvine, the Labour Lord Chancellor, of mixing politics and the law by insisting on sitting as a judge in the House of Lords while also serving as a minister, thus putting the impartiality of the final court of appeal at risk. Steyn believed that it was a blatant breach of separation of powers, and impossible to justify in principle or in practice.

Although Steyn was a highly esteemed judge, some felt that his strong liberal views should have been kept more closely in check. On one occasion, when hearing appeals to the Privy Council from Commonwealth countries where capital punishment still prevailed, he tended to stretch the law to accommodate his own strong opposition to the death penalty. Some also thought, especially after the 1997 election, that his public pronouncements added unhelpfully to the tension in the already strained relationship between Blair’s government and the judiciary.

Impressive achievements aside, Steyn was also directly responsible for making the criminal offence of assault what it is today. In the House of Lords he upheld a Court of Appeal decision that silence can amount to an assault and psychiatric injury can amount to bodily harm. The case itself involved a defendant who made a number of silent telephone calls over three months to three different women, causing fear.

A champion of the 1998 Human Rights Act, he managed to weave it into the fabric of the legal system transforming the country into “a rights-based democracy”.

Anthony Lester, QC, said: “He had a terrier-like tenacity, deeply-held convictions and the courage of a lion. He’s going to be extraordinarily difficult to replace.”

Over the years, Steyn served on charitable and educational bodies such as the Race Relations Committee of the Bar and the Lord Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on Legal Education and Conduct.