WP: Biden has a historic chance to end war on Iraq

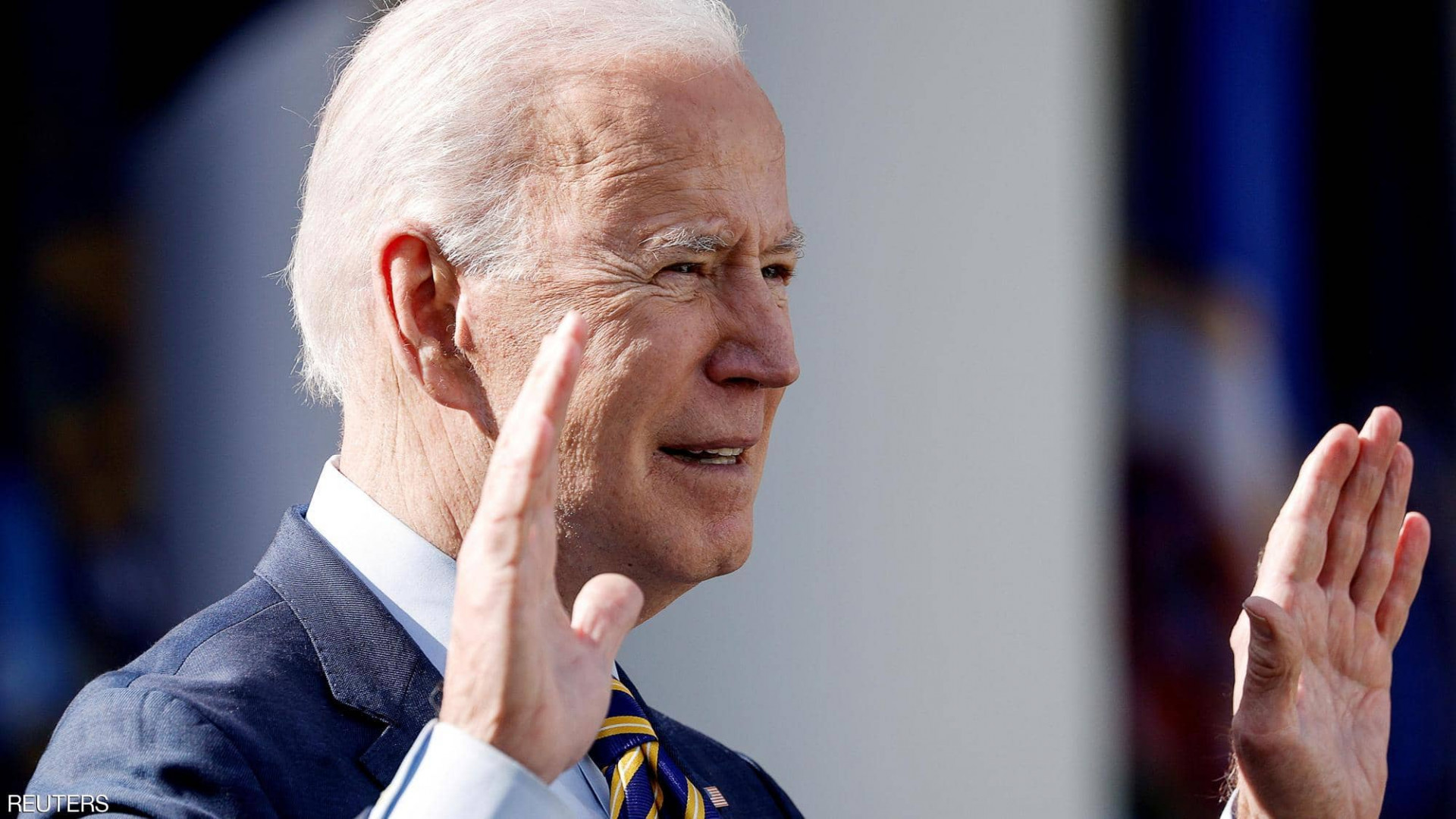

Shafaq News/ President Biden withdrew U.S. forces from Afghanistan this summer and drove a trillion-dollar infrastructure package through Congress with bipartisan support, goals that eluded his two immediate predecessors. Now, he may get a chance to formally end the war in Iraq.

Under legislation being put together in fits and starts, Biden could be in a position to cancel the two-decades-old congressional measure that provided the March 2003 invasion’s legal rationale, the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) lawmakers adopted in October 2002.

Doing so will require the bitterly divided Congress to do its part by getting the proposal to his desk, so don’t bet the cryptocurrency farm just yet. But for the first time since 9/11, a president may actually take concrete steps to rein in, not expand, executive branch war-making powers.

NDAA is the current path

Last night, Senate Republicans delayed a final vote on the National Defense Authorization Act of 2022, which is expected to serve as the vehicle for the AUMF repeal. But the NDAA is generally considered must-pass legislation, meaning it’s likely to find its way through congressional hedgerows and reach Biden’s desk sooner or later.

Democrats hope to attach a proposal from Sens. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) and Todd C. Young (R-Ind.) that would scrap the 2002 AUMF and a companion AUMF from 1991. Both authorized U.S. military action against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Both remain on the books after his death.

They’ll have to overcome opposition to the bipartisan legislation from Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), who argued in mid-November that passing it would “weaken the authorities that support our military’s presence and operations flexibility.”

And, back in June, McConnell correctly argued that administrations of both parties — Democratic President Barack Obama, Republican President Donald Trump — had invoked the 2002 AUMF for conflicts “far beyond the defeat of Saddam Hussein’s regime.”

That’s true. Obama cited the measure as part of his legal justification for military action against ISIS. Trump did so as part of his legal justification for the airstrike in Iraq that killed Iranian Gen. Qasem Soleimani, even pointing in a footnote to Obama’s rationale.

Bipartisan backing

Supporters of repealing the measure say just because presidential overreach on matters of national security is bipartisan doesn’t make it right.

“Repeal is crucial because the executive branch has a history of stretching the 2002 AUMF’s legal authority,” House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Gregory W. Meeks (D-N.Y.) said in June. “It has already been used as justification for military actions against entities that had nothing to do with Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist’s dictatorship.”

Meeks’s comments came as the House voted to repeal the 2002 AUMF by 268-161, with 49 Republicans joining 219 Democrats in favor.

Days before the vote, Biden had come out again in favor of repeal.

"The administration supports the repeal of the 2002 AUMF, as the United States has no ongoing military activities that rely solely on the 2002 AUMF as a domestic legal basis, and repeal of the 2002 AUMF would likely have minimal impact on current military operations," the White House said in a policy statement.

While that reads as a rebuttal to McConnell — and it is — that “solely” is important. Since taking office, the Biden administration has mostly leaned on his status as commander in chief under Article II of the Constitution, not the 2002 AUMF, to justify repeated strikes at Iranian-backed militias in Iraq and Syria.

“The Commander in Chief, under Article II, has not only the authority but the obligation to protect American forces in combat theaters and in military operations. So clearly, under U.S. constitutional authorities, this was right there,” Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said in February.

So while the Biden administration says repealing the 2002 AUMF won’t affect any ongoing military operations, it's also not using the authorization to justify new strikes, either, raising the question of whether repeal would have much, if any, direct effect on America’s use of force.

In a way, the true test of Biden’s philosophy of when, where and under what circumstances he can send young Americans into deadly danger may be congressional efforts to rewrite the 2001 AUMF that has underpinned the entire war on terrorism for two decades across nearly every continent.

In his confirmation hearing, Secretary of State Antony Blinken testified the authorizations on the books needed to be reworked, including the one from 2001.

“It’s long past time that we revisit these and review them,” Blinken said. “We did try to do this a few years ago. And it’s not easy to get to yes.”

But the White House policy statement from June hints at administration reservations.

“In working with the Congress on repealing and replacing other existing authorizations of military force, the Administration seeks to ensure that the Congress has a clear and thorough understanding of the effect of any such action and of the threats facing U.S. forces, personnel, and interests around the world,” the statement said, in what sounded like a warning not to hamstring the executive branch.

And that, of course, is why it’s taken until 2021 — possibly 2022 — to repeal the 2002 authorization to topple long-gone Saddam.

By Oliver Knox for the Washington Post