Report: Iraq’s prime minister is sending mixed messages on whether US forces should withdraw or not

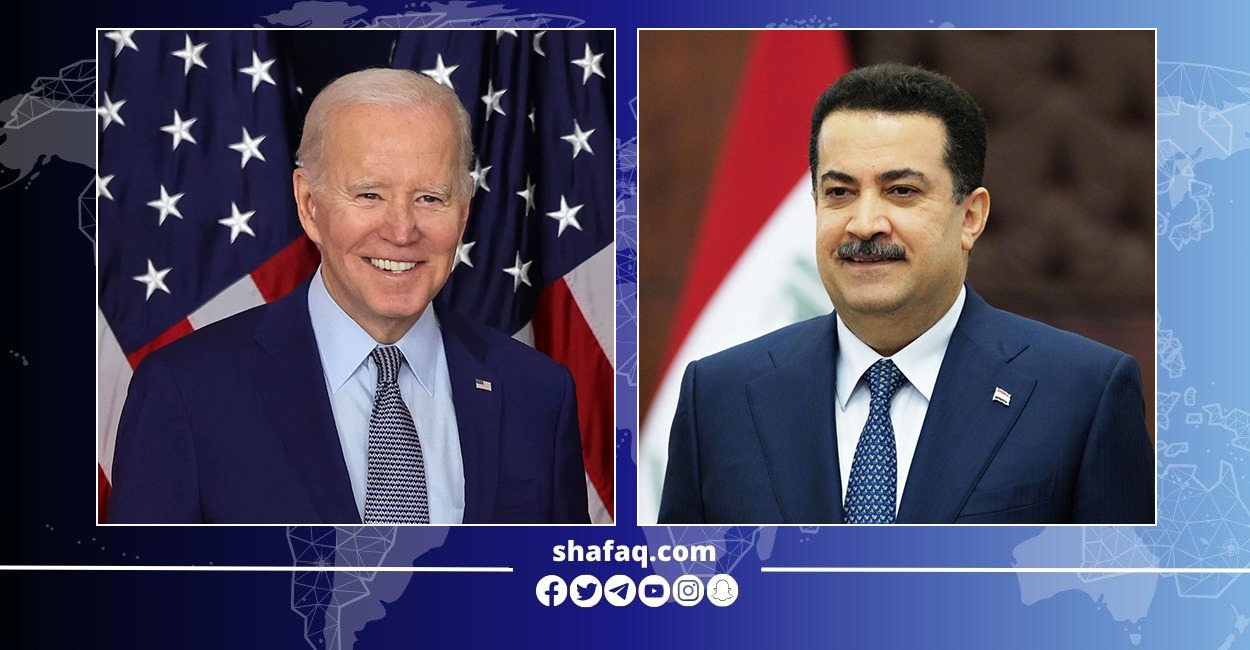

Shafaq News/ After a year of stability and mutual tolerance, US-Iraq relations have taken a turn for the worse in the last two months. When President Joe Biden took office in 2021, the general belief was that US policy toward Iraq would be shaped by diplomacy, as opposed to the heavy-handed approach of the Donald Trump administration, which included threats of sanctions, asset confiscation, and the use of force to settle scores on Iraqi soil without the consent of Iraq. Former Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi was a staunch advocate of working closely with all international actors, particularly the United States, and transformed Iraq into a constructive regional player and an agent of stability; for example, Iraq successfully mediated complex conflicts, such as the longstanding Iran-Saudi Arabia dispute. As a result, Kadhimi enjoyed a robust relationship with the Biden administration. However, Kadhimi’s successor, Mohamed Shia al-Sudani, has not enjoyed a similar level of trust during his premiership since it began in October 2022.

Despite securing a year-long truce between the US and the Iraqi political and armed groups that reject the US military presence in Iraq, and receiving the Biden administration’s declared support for his government, Prime Minister Sudani has not traveled to Washington. Now, with the security truce dissolved following the Israel-Hamas war since October 7, 2023, and the tit-for-tat drone strikes in the past weeks, Sudani is unlikely to be received in the White House soon, if ever.

The invitation US Secretary of State Antony Blinken extended to Sudani in September 2023 “to visit the White House soon” will be frozen under the current tense relations and as President Biden’s calendar becomes increasingly crowded in the months leading to the November presidential election. Meanwhile, it would not be an exaggeration to state that US-Iraqi relations are rapidly approaching the dynamics observed under the Trump administration in 2020, when a US drone strike killed the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani and Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) Deputy Commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis. This led the Iraqi Council of Representatives to pass a resolution calling for the withdrawal of US forces from Iraq.

On January 4, a US drone strike inside Baghdad killed Mushtaq Jawad al-Saeedi, the deputy commander of Baghdad Belt for the PMF, who belongs to Harakat al-Nujaba, an armed group that is closely associated with Iraq and designated by the US as a terrorist group. The drone strike coincided with the Iraqi activities commemorating the fourth anniversary of the assassination near the Baghdad International Airport, which killed several Iraqis and Iranians, including Soleimani and Muhandis.

The Iraqi Presidency, the Prime Minister’s Office, and the Foreign Ministry issued three separate statements condemning the latest drone attack, calling it a violation of Iraqi sovereignty and a breach of the bilateral agreement on the rules of engagement and the terms of the presence of US forces in Iraq. Major General Yehia Rasool, the spokesperson of the Commander-in-Chief of Iraqi Armed Forces, described the drone strike in the following terms: “In a blatant aggression and violation of Iraq’s sovereignty and security, a drone conducted an act akin to terrorist activities.”

In his daily briefing at the Pentagon on January 4, Air Force Major General Pat Ryder reiterated the often-cited basis for the presence of US forces in Iraq: they are in the country at the invitation of the government of Iraq and they are stationed there “for one reason, which is to support the defeat-ISIS [Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham] mission.” He added that the US will “continue to work very closely with our Iraqi partners when it comes to the safety and security of our forces. When those forces are threatened, just like we would anywhere else in the world, we will maintain the inherent right of self-defense to protect our forces.”

However, this “inherent right of self-defense” has caused a bilateral crisis every time it has been exercised in Iraq. The Iraqi government’s reaction was articulated by Prime Minister Sudani, who called the January 4 drone strike “a crime” and said, “we affirmed our standing and principled position regarding ending the presence of the International Coalition after the end of the justifications of its presence, and we are working on setting a time to start the dialogue through the bilateral committee that was established to define the arrangements for ending this presence, and this is a commitment the government will not back down from.”

The Iraqi government took another unusual step: sending a text message surveying average Iraqis for their opinion on the matter. “Dear citizen, do you support the continuation of the International Coalition’s mission in Iraq?” the text read. A polling center sent the message, but the link people needed to click in order to give their answers led to a website administered by the government.

Despite this and the many strong statements made in the past few days, the Iraqi prime minister sent a soothing message to the United States while speaking to the press. On January 10, Sudani told Reuters that the upcoming talks to negotiate an end to international forces’ presence in Iraq “is not a discontinuation of the partnership between Iraq and the International Coalition, but a beginning of bilateral relations between Iraq, the US, and other countries, including security relations. We have no reservations on signing bilateral security agreements for general security cooperation or for training and capacity building purposes.”

The coming few months will reveal whether the Iraqi government intends to uphold the position Sudani announced and make an official request to withdraw US forces or, as skeptics claim, Sudani’s statement was made for domestic consumption.

What made an already tense situation worse was Major General Ryder’s statement to journalists at the Pentagon daily briefing on January 4: “We do know that the Iraqi security forces have continued to assist in identifying in some cases where these Iranian proxies have conducted attacks against US forces, and we are appreciative of that support.”

Prime Minister Sudani’s Iraqi opponents interpreted this as an accusation that Iraqi security forces were working as informants to aid the US airstrikes. The Prime Minister’s Security Media Cell issued a press release calling Ryder’s statement a deception attempt, adding, “We firmly deny the existence of such cooperation, but the opposite is true, yesterday’s aggression was executed directly without informing the knowledge of any Iraqi security or military entity.”

It is hard to explain how US government officials, who insist that the presence of US forces in Iraq is based on the invitation of Iraq’s government, fail to see the irony in the unanimous condemnations of their acts coming from all Iraqi leadership quarters. By the same token, it is also hard to explain how the Iraqi government, which validates the claim of their invitation of US forces, fails to protect its “guests” from attacks by groups it describes as Iraqi security forces, which are supposed to be working according to the authorities granted to them by the commander-in-chief. It is high time the governments of Iraq and the United States review and uphold their respective obligations instead of waffling between partnership and belligerence.

(By Dr. Abbas Kadhim for the Atlantic Council)