Shafaq News – Diyala

Iraq’s architectural heritage is entering a dangerous phase as increasingly forceful storms collide with structures already weakened by decades of neglect. What the weather exposes is not only physical deterioration, but the slow unraveling of the cultural fabric these historic sites once held together.

Diyala became the latest warning sign when heavy rainfall flooded Baqubah’s historic Saray (Palace). Widely regarded as one of the city’s remaining Ottoman-era administrative buildings, the Saray is believed to date to the late 19th or early 20th century, when Baqubah served as an important district center in Diyala. Like other sarays built in the final years of Ottoman rule, it functioned as the seat of local governance before evolving into a civic and cultural venue. In recent decades, it has hosted artistic and literary unions, preserving its role as a living landmark.

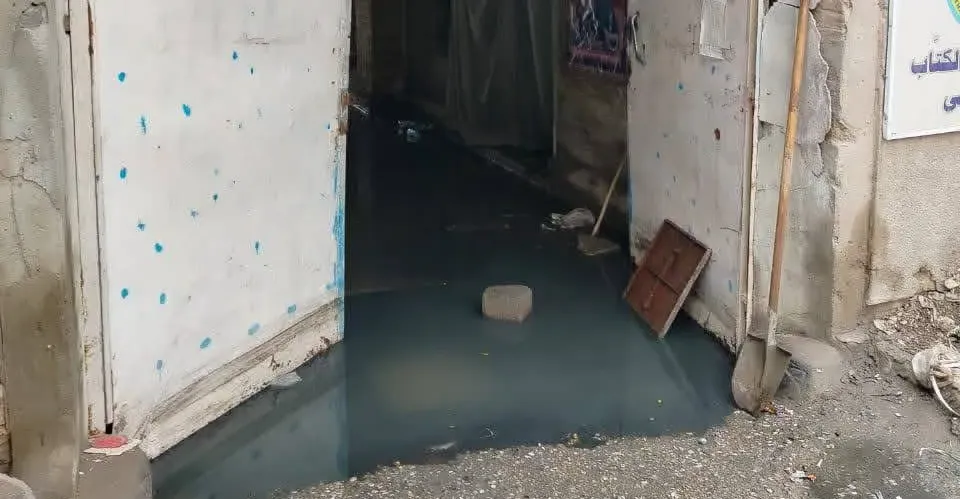

The complex was overtaken after the province’s failing wastewater network collapsed under the surge. Contaminated water forced its way through the entrance, swept across the ground floor, and reached the guardroom that once greeted visitors. The damage appeared abrupt, yet for those familiar with the structure, it simply confirmed years of unaddressed vulnerability.

Adnan Ahmed, head of the Iraqi Artists Syndicate in Diyala, said the Saray now faces the risk of collapse. “We warned the authorities more than once, but nothing happened,” he told Shafaq News, noting that all cultural activities have been suspended because the building can no longer be trusted to withstand future storms.

The Saray’s flooding reveals a broader reality: climate stress is accelerating the breakdown of heritage sites already pushed to their limits by weak infrastructure and inconsistent preservation efforts. Much of Iraq’s urban network was never designed to absorb today’s storm patterns, and when drainage systems fail, it is the country’s oldest structures—those that carry its historical memory—that bear the brunt of the damage.

For many Iraqis, what erodes is not only stone and timber. These buildings held gatherings, hosted performances, and anchored the daily rituals that shaped collective identity. When a place like the Saray falters, a community loses more than the structure—it loses a point of continuity, a physical connection to stories passed across generations.

Ahmed hopes the recent disaster will break through years of inaction. He is calling for reinforcement of the Saray’s foundations, upgrades to the drainage system, and changes to the site’s elevation to protect it from future storms. His appeal reflects a growing concern among cultural workers that Iraq is running out of time to safeguard what remains.

In Baghdad, traditional houses—once defined by intricate wooden carvings and shaded courtyards—have vanished after decades of wear and unlawful alterations, while in Mosul’s Old City, the fractures left by war deepen each rainy season, threatening Ottoman-era homes, churches, and markets that restoration teams have yet to fully revive.

Basra’s iconic shanasheel, whose wooden balconies once shaped the city’s visual identity, now deteriorate under the weight of humidity and rising salinity. Meanwhile, in Najaf and Karbala, entire historic quarters are disappearing as commercial expansion reshapes the urban core, leaving the remnants exposed to both development pressure and seasonal flooding.

Read more: Archaeological Armageddon: Climate change threatens Iraq's unexcavated history