Shafaq News

For more than six decades, popes have walked into the Middle East’s most volatile landscapes, choosing war-torn cities, occupied territories, and fragile states as the front lines of their diplomatic and spiritual missions. From Paul VI’s groundbreaking pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1964, through John Paul II’s sweeping regional tours, to Pope Francis’s unprecedented walk-through Mosul’s ruins in 2021, the Vatican has consistently positioned itself within the moral and political storms of the region.

Today, Pope Leo XIV continues that trajectory with his first foreign visit to Turkiye and Lebanon in late 2025, arriving at a moment when conflicts, demographic collapse, and regional realignments are reshaping the Middle East’s social fabric.

The Vatican has no army, no economic leverage, and no territorial authority in the region, yet its presence carries disproportionate weight. Papal visits function simultaneously as symbolic interventions, political messages, and pastoral gestures. They attempt to influence narratives, support minorities, and restore a sense of visibility to communities that feel erased by war, occupation, and state decay. The central question remains whether these highly symbolic trips produce tangible effects—or whether they simply illuminate, for a brief moment, crises that remain locked in place.

No part of the Middle East reveals the stakes of papal diplomacy more starkly than the demographic decline of Christian communities. A century ago, Christians made up more than 13 percent of the region. Today, they represent roughly five percent. Lebanon still holds the highest proportion of Christians among Arab states, with various estimates placing them between 32 and 40 percent of the population, despite the absence of an official census since 1932. Even so, sustained emigration, economic collapse, and political fragmentation are reshaping Lebanon’s communal balance.

Iraq’s decline is even sharper: before 2003, the country was home to more than one million Christians; today, between 300,000 and 500,000 remain. In Palestine, and particularly in Gaza, the situation is even more dire. The West Bank still maintains a small but rooted Christian community, but Gaza’s Christians now number around one thousand people, less than one-tenth of one percent of the population.

Gaza’s ongoing war has accelerated this fragility. Since the conflict erupted last year, the Gaza Strip has endured relentless Israeli bombardment, mass displacement, and one of the fastest humanitarian deteriorations in its modern history. The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics reported that Gaza’s population has fallen by roughly six percent since the war began, driven by more than 70,000 casualties, hundreds of thousands of displacements, and the near-total collapse of basic services. Churches in Gaza report staggering losses with at least 44 Christians killed since the start of the war—an enormous toll for such a small community. Some died directly from the Israeli bombardment; others succumbed to injuries or the inability to access medical treatment.

Many families sheltering inside the Holy Family Church compound, living under siege conditions, unsure whether their community will survive at all. Local leaders warn that if the war continues, Gaza may lose its ancient Christian presence entirely.

This devastation forms the backdrop to Pope Leo XIV’s arrival in Lebanon, a country grappling with economic ruin, institutional paralysis, and demographic erosion. Once described by John Paul II as “more than a country, a message,” Lebanon now lives in the shadow of its own collapse. Its currency has lost nearly all value, public institutions barely function, and the middle class—once strongly anchored by Christian professionals—has fractured under the weight of emigration. Many Lebanese Christians see the Pope’s visit not only as a pastoral moment but as a rare signal that the world still notices their struggle.

Lebanon’s internal crisis is compounded by escalating tensions along its southern border, Beqaa, and Beirut. Between mid-September and mid-November 2024, the Ministry of Health reported 3,583 fatalities, including 231 children, killed by Israeli bombardment. Even the ceasefire announced in late November 2024 failed to halt the attacks. Israeli operations resumed within days, claiming more than 350 additional lives.

In such an atmosphere, Leo XIV’s arrival carries significant symbolic weight. For many Lebanese Christians, Sunnis, Shias, Druze—the papal visit signals that their country has not been abandoned to instability and conflict.

Papal visits to crisis regions have never been purely ceremonial. Pope Francis demonstrated this when he visited Mosul in March 2021, standing amid the ruins left by ISIS and declaring that “fraternity is stronger than fratricide; peace is stronger than war.”

In November 2025, Pope Leo XIV echoed the same moral imperative when he entered Istanbul’s Armenian Cathedral, urging both Christians and Muslims “not to surrender to the logic of revenge.” These moments reflect a Vatican understanding that physical proximity to suffering is itself a diplomatic act.

Historically, the Vatican’s engagement with crisis zones developed in stages. Paul VI’s visit to Jerusalem in 1964—ending more than a millennium of papal immobility—opened a new era of personal diplomacy, anchored in his plea: “No more war, never again war.” John Paul II later expanded this model into a global mission. His 1979 visit to Turkiye emphasized Christian–Muslim understanding; his 1997 visit to Lebanon reaffirmed pluralism after the civil war; his 2000 journey to Palestine and Israel balanced empathy toward Holocaust victims at Yad Vashem with solidarity for refugees in Bethlehem; and his 2001 visit to Syria included an unprecedented moment inside the Umayyad Mosque.

Benedict XVI’s papacy confronted heightened tensions between the Islamic world and the West. His 2006 visit to Turkiye, including silent prayer inside the Blue Mosque after the Regensburg controversy, became a milestone in repairing interreligious relations. His 2009 trip to Palestine and 2012 visit to Lebanon emphasized citizenship equality and the protection of Eastern Christianity.

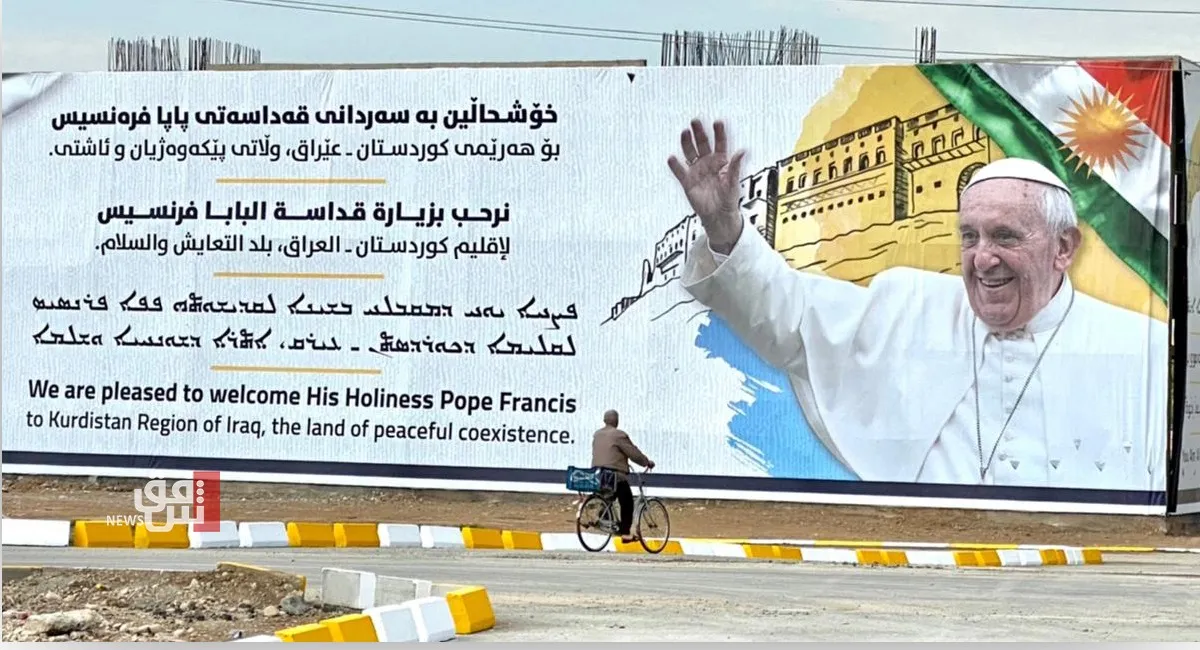

Francis adjusted the model once again. His 2017 visit to Egypt strengthened ties with Al-Azhar at a moment of rising extremism. His 2019 visit to the UAE produced the Document on Human Fraternity, co-signed with the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, redefining coexistence as a global mandate. His 2021 visit to Iraq—described by analysts as the most dangerous papal trip in modern history—brought him to Najaf for a historic meeting with Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, followed by Mosul, Qaraqosh, Baghdad, and Erbil. The trip repositioned Iraq as a central arena in the Vatican’s vision of interfaith coexistence.

Reactions to these visits often unfold across multiple layers. Governments frequently view the Pope’s arrival as a form of international validation. During Francis’s visit to Baghdad, Iraqi officials told Shafaq News that the trip signaled “Iraq’s return to the world,” reflecting renewed capacity to host global figures after decades of turmoil. Lebanese officials now express similar expectations. One senior figure told Shafaq News that “a papal visit is sometimes worth more than a donor conference,” framing Leo XIV’s visit as a catalyst for global attention.

Hikmat Dawood, an Iraqi Christian diplomat, said the pope’s visit to Beirut carries two parallel messages. On the religious level, he viewed the trip as an appeal for peace within the Christian community itself — “an effort to bring the various churches closer, reduce internal disputes, and identify common ground.” Such unity, he argued, strengthens the ability of Christian groups to articulate their demands when dealing with governments in a region where Muslim majorities shape political life.

Pope Leo XIV and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I offer an Ecumenical Blessing at the Patriarchal Church of St. George in Istanbul, highlighting the fraternity and communion between the Churches of Rome and Constantinople. pic.twitter.com/tp3jeXcAGb

— Vatican News (@VaticanNews) November 30, 2025

Politically, Dawood described the visit as a gesture of solidarity amid the ongoing conflict in Gaza and the wider region. He said the pope’s presence signals support for de-escalation and for efforts aimed at restoring stability, framing the visit as part of a broader call to reduce violence and revive prospects for peace.

Religious institutions interpret papal visits as a form of protection. For minority Christian communities—Chaldeans and Assyrians in Iraq, Maronites and Armenians in Lebanon, Armenian and Syriac communities in Turkiye—the Pope’s presence publicly asserts their historical and political relevance. After Francis’s visit, Patriarch Louis Raphael Sako told Shafaq News that the Pope’s presence reminded Iraqis that “this country needs its Christians,” a message that resonated deeply in areas devastated by ISIS.

Ordinary citizens tend to respond on an emotional level. In Mosul, a resident told Shafaq News in 2021, “For the first time in years, I feel we are not forgotten.” The same sentiment is emerging in Lebanon. In Beirut’s Ashrafieh district, a young pharmacist told Shafaq News that she hopes “the Pope will remind the world that Lebanon’s people are exhausted, not defeated.” A teacher from Tyr asked, “Will he speak about the fear we live with every night under the Israeli drones?” Their questions reveal how papal visits can momentarily counter the psychological isolation that crisis states produce.

The deeper question remains whether these visits produce lasting change. Analysts note that in states like Iraq and Lebanon, symbolic actions can acquire political weight precisely because they occur in environments where institutions are weak. A papal visit challenges the narrative that Christians are disappearing and pressures governments to protect heritage and religious sites. Church leaders in Iraq told Shafaq News that after Francis’s visit, “people delayed their decision to leave because they felt seen again,” highlighting the psychological impact on migration patterns.

Dr. Saad Salloum, an Iraqi expert on religious diversity, told Shafaq News that the visit carries unusual political and religious weight at a moment when Christian demographics are declining, violence against minorities in Syria persists, and a wider regional war continues to unfold.

According to Salloum, the visit comes amid rising geopolitical tensions, worsening economic conditions, and deepening existential fears across religious and ethnic groups. In this environment, he said the papal message takes on a broader political function: easing polarization, reopening channels of communication between rival actors, and issuing a call that may help reduce the risk of further deterioration or a slide into wider confrontations.

Politically, papal visits do not rewrite laws or end conflicts, but they can create short “windows of calm.” During Francis’s trip to Iraq, rival groups temporarily de-escalated tensions. Internationally, such visits draw intense media attention, forcing policymakers to refocus on crises that might otherwise drift into obscurity. The meeting between Francis and al-Sistani, widely covered by global outlets, strengthened public discourse around coexistence without requiring legal change.

Religiously, the impact is even stronger. John Paul II’s recognition of Islam as a partner in peace, Benedict XVI’s reconciliation gestures in Istanbul, Francis’s global fraternity initiative, and Leo XIV’s emphasis on unity and healing in 2025 all contribute to a Vatican theology that positions coexistence not as an aspiration but as a moral obligation.

"We must strongly reject the use of religion for justifying war, violence, or any form of fundamentalism or fanaticism."Joined together with 27 other leaders of Christian Churches to commemorate the 1,700th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council in the Church’s history,… pic.twitter.com/Bl0V5I0wnk

— Vatican News (@VaticanNews) November 28, 2025

Leo XIV’s visit to Lebanon amplifies this trajectory. Bishop George of the Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Beirut told reporters that “the Holy Father is coming at a very difficult moment for Lebanon,” adding that many Lebanese “still fear a possible return to all-out war with Israel.” Yet he emphasized that the visit is “a sign of hope,” proof that Lebanon remains on the global moral map.

Hezbollah, in a rare gesture of convergence, urged the Pope to denounce “injustice and aggression” and encouraged supporters to line the road from the airport to the presidential palace. Even from neighboring Syria, a delegation of about 300 Christians prepared to travel to Beirut for the Pope’s public mass and meeting with youth groups.

These reactions mirror the Vatican’s long view of crisis diplomacy. Papal visits cannot end wars, repair collapsed states, or reverse demographic decline. But they can recalibrate expectations, uplift endangered communities, and remind global audiences that the people living through these crises still matter. In a region where forgetting often precedes disappearance, visibility becomes a form of political protection.

As Pope Leo XIV stands in Beirut—surrounded by economic collapse, border anxieties, and the devastation of the Gaza war—the meaning of papal diplomacy becomes unmistakable. In crisis countries, the visit itself is the message. It does not close wounds, but it prevents them from being erased. And in a region where erasure threatens to become destiny, that act alone can be politically and spiritually transformative.

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.