Shafaq News

In the modern political memory of Iraqi Kurdistan, Nechirvan Barzani occupies an unusual space. He is neither the romantic insurgent of old legends nor the modern populist who rallies public squares by force of charisma. Instead, he is a practitioner of balance—an operator who prefers the corridor next to the stage, the handshake to the headline, and incremental gains over dramatic standoffs.

That quiet style helped produce what many in the Kurdistan Region came to describe as a “golden decade” after 2003: a period of relative security, expanding services, an opening to the world, and an attempt—imperfect, often contested—to shift politics from party trenches to state institutions.

This profile traces that project and its limits: how a politician rooted in the Barzan mountains learned to turn measured steps into policy—without romanticism and without erasing the system’s structural weaknesses.

Roots and Formation

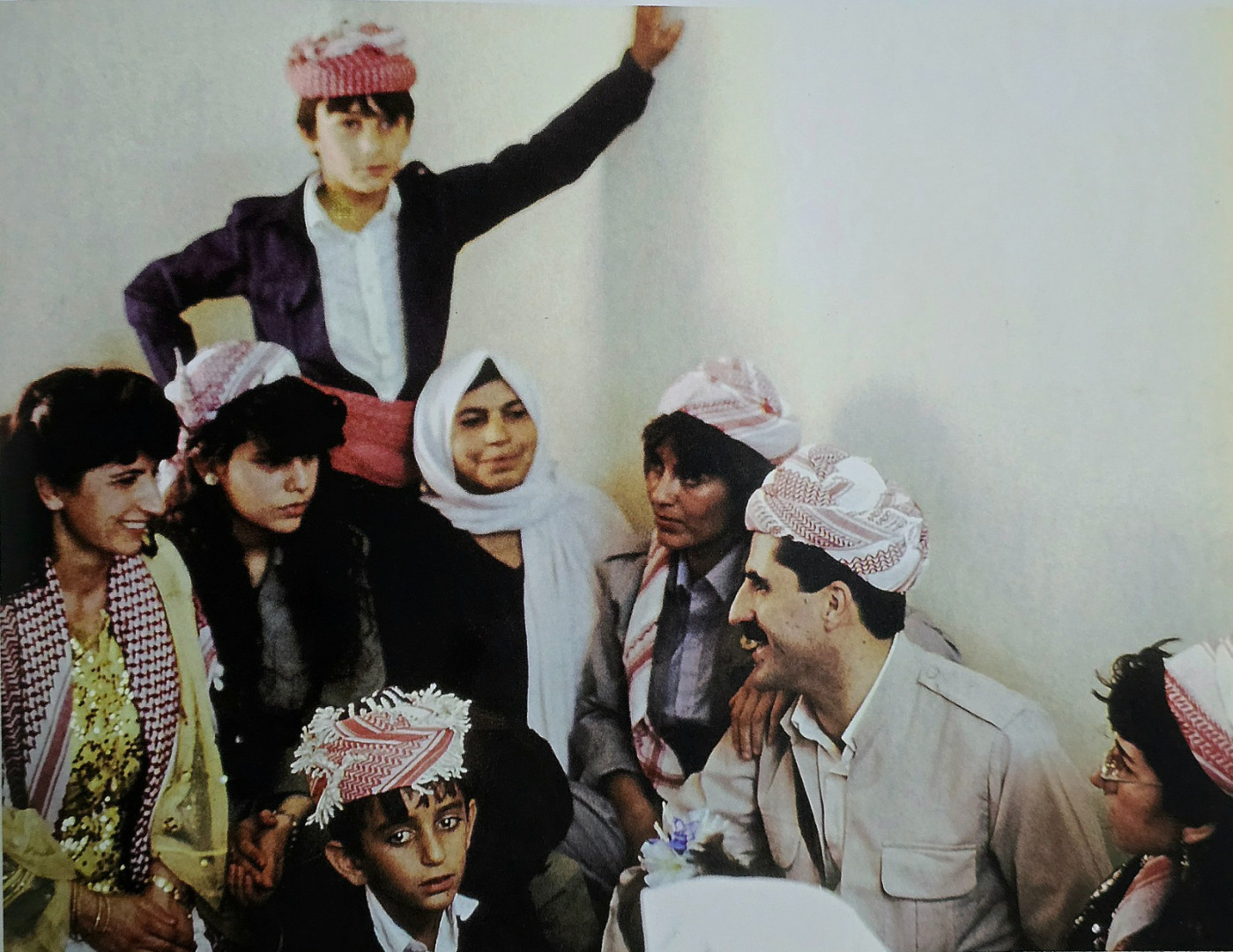

Nechirvan Idris Barzani was born on September 21, 1966, in Barzan, a village north of Erbil known as much for its rugged geography as its political lineage. His grandfather, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, is the central figure of twentieth-century Kurdish nationalism in Iraq and the founder of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the largest political force in the Region. His father, Idris Barzani, bridged battlefield politics and negotiation, arguing that institutions had to be built alongside resistance.

The family environment resembled a permanent situation room more than a private home—negotiations with Baghdad, tribal mediation, and logistics of war were frequent topics. The 1975 Algiers Agreement between Iraq and Iran—collapsing the Kurdish rebellion—pushed the Barzanis into exile.

Nechirvan spent formative years in Iran, moving between Karaj and the Kurdish regions in the west. He absorbed Persian, encountered a different bureaucratic culture, and witnessed a revolution’s aftermath. Those years added range: Kurdish in identity, conversant in Persian political idiom, later fluent in Arabic and English.

By the mid-1980s, he was already engaging with Kurdish student circles in Iran, where debates on governance and diaspora politics foreshadowed the technocratic streak that would later mark his leadership.

The multilingualism and exposure to multiple centers of power—Ankara, Tehran, Baghdad, and Western capitals—would become professional assets when the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the autonomous authority established after the 1992 elections and later anchored in Iraq’s 2005 constitution, sought external partnerships.

Following the 1991 Kurdish uprising and the creation of a de facto safe zone in much of northern Iraq, the Barzanis returned. Nechirvan’s rise through the KDP apparatus was swift: by 1989, he was on the Central Committee and soon after joined the Political Bureau.

Unlike peers who cultivated public charisma, he leaned toward management and planning. Masoud Barzani, his uncle and KDP leader, channeled him early into governance portfolios—economic rehabilitation, public services, and institutional design—areas where he could be evaluated on delivery rather than rhetoric.

The ethos he absorbed from Idris Barzani’s generation—build institutions even in adversity—would become his own grammar of politics. As he would later put it in a 2007 speech to civil servants: “The building of our homeland will only be complete when hearts and positions come together.”

From Party Habits to State Templates

When Nechirvan Barzani assumed the premiership in 1999 in Erbil, Kurdistan was still bifurcated by the scars of the 1994–1998 intra-Kurdish conflict between the KDP and its chief rival, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), the second-largest Kurdish party founded in 1975. The split produced parallel administrations. The challenge was not only reconstruction, but also the partial depoliticization of government machinery.

He favored a “quiet transition” strategy: slowly widening the space for technocrats, standardizing procedures, and signaling that ministries should answer to a cabinet and not only to party offices.

Records show that during his first premiership (1999–2009), the number of technocrats holding ministerial or deputy ministerial posts doubled compared to the early 1990s party-era cabinets.

Symbolism mattered for Nechirvan. He brought women and representatives of smaller communities into cabinet posts and senior roles—an early indication that the Region would be framed publicly as a political mosaic rather than a monochrome project.

Inside government, committees and rotating leadership posts—imperfect but visible—nudged decision-making toward collective forms. Outside, he pursued reconciliation with the PUK headquartered in Al-Sulaymaniyah, preparing the ground for the 2006 unification of the dual KRG administrations. That step, while far from eliminating party rivalry, gave the Region a single institutional face for legislation, budgeting, and external outreach.

The template that emerged did not claim a clean break from party politics; no such rupture occurred. Instead, it used institutions to discipline competition and make it predictable, rewarded coalition partners with inclusion, and kept adversaries at the table, even if only on minimum terms.

The method relied on patience, the routinization of meetings, and a preference for compromise over brinkmanship.

Economy as Governance Tool

In the early 2000s, daily life in Kurdistan was still fragile: electricity shortages, degraded roads, and limited administrative capacity. Nechirvan’s governing argument was straightforward: legitimacy comes from delivery. He linked state-building to visible services—paying salaries, expanding electricity supply, paving roads that shortened travel between rural districts and city markets, and opening airports to connect Erbil and Duhok to the outside world.

A cornerstone was the 2006 Investment Law, which offered tax incentives and legal guarantees to draw capital, and the creation of the Kurdistan Board of Investment to shepherd projects.

According to the Board of Investment, more than 600 licensed projects worth over USD 30 billion were approved between 2006 and 2013, reshaping the skylines of Erbil and Duhok.

The aim was not construction for its own sake, but a middle-class foundation for stability—an ecosystem where private firms, universities, and a growing service sector could absorb young graduates instead of pushing them toward emigration or public-payroll dependency.

Energy policy gave the Region leverage. Starting in 2007, the KRG signed production-sharing contracts with firms such as DNO and Genel Energy, eventually enabling exports through a 2013 pipeline to Turkiye’s Ceyhan. Baghdad objected repeatedly, and the dispute remains one of the most sensitive files in federal politics, bound up with interpretations of the constitution and federal court rulings.

By 2013, exports through the pipeline had reached roughly 280,000 barrels per day, though Baghdad insisted all sales had to pass through the State Oil Marketing Organization (SOMO).

From Nechirvan’s perspective, however, without the ability to monetize resources—within or alongside federal arrangements—the Region would remain vulnerable to budget cuts originating in national politics. The pipeline created both revenue and risk: revenue when prices and flows cooperated; risk when courts, federal ministries, or geopolitics interrupted exports.

The 2014 oil price collapse and the war against ISIS—which absorbed budgets and flooded the Region with displaced families—forced crisis management: austerity measures, arrears to public employees, short-term borrowing, and improvised revenue tools.

Critics read the turbulence as proof that the model over-weighted oil and real estate. Supporters argued that in the absence of the earlier build-out of roads, power, and airports, the Region would have cracked under the humanitarian strain.

Both points contain truth. What is clear is that the economy, in Nechirvan’s hands, doubled as diplomacy: “every investor became a messenger to their home capital that Kurdistan was a place where contracts could be honored and people could land safely,” he said on an occasion.

His economic view was never framed as a spreadsheet alone. He articulated it in social terms: a functioning economy must reach the last classroom and the furthest clinic. He often told ministers that budgets were not abstractions but daily guarantees of credibility—summed up in his pragmatic line on public servants: “It is a basic and natural right of employees to be paid.”

Schools, Universities, and a Pact of Stability

The most durable shift of the post-2003 era may not be measured in barrels or building permits, but in classrooms. Nechirvan framed education as security by other means: if young people saw a future in their own towns and cities, the politics of grievance could be tempered.

Between 2003 and 2013, primary school enrollment increased by nearly 40%, according to KRG Education Ministry data, with the gender gap in early grades dropping to less than 5%.

A Private Schools Law in 2012 codified standards for a fast-growing sector, including international-curriculum institutions. As he liked to say in policy forums: “Education is the backbone of any living society.”

Before 2003, the Region had three public universities (Salahaddin, Sulaimani, Duhok). Within a decade, a network took shape: Hawler Medical University (2005); Kurdistan University–Hewlêr (2006), the first public English-language university; Soran and new universities in Zakho, Raparin, Garmian, and Halabja; polytechnic universities in each province; and private institutions such as American University of Iraq–Sulaimani and Cihan University of Sulaimaniya.

By 2014, the total number of universities in the Region—public and private—had surpassed 30, compared to just three before 1992.

Degree programs shifted toward medicine, engineering, and applied sciences, and scholarship schemes sent cohorts to Turkiye, Europe, and North America. The goal was not elite credentialing but workforce alignment—producing technicians and professionals for the Region’s hospitals, construction sites, energy fields, and municipal services.

Language policy combined identity and openness: Kurdish remained the core medium, but Arabic classes served displaced families and helped inter-Iraqi mobility, while English and French expanded as global gateways. For readers beyond Iraq, the significance is simple: the KRG sought recognition as authentically Kurdish while signaling compatibility with international business, health, and academic standards. That combination—local roots and external fluency—became part of Nechirvan’s political brand.

His educational approach intersected with a larger social message. In a single line that echoed across schools, stadiums, and book fairs, he summarized the “pact of stability”: “Every school that opens, every stadium that lights up, every book that is printed is another stone in the wall of peace.”

Youth, Culture, and Sports: Building Civic Texture

Physical reconstruction and school expansion did not automatically translate into reasons to stay. Nechirvan’s teams tried to widen the civic ecosystem: youth centers, small business programs, public libraries, and municipal theaters.

Grants and partnerships with consulates supported book fairs and translation initiatives. The Erbil International Book Fair evolved into a recognizable regional event, bringing Iraqi, Kurdish, and foreign authors to the same halls.

Sports were leveraged as social infrastructure. Clubs such as Erbil SC and Duhok SC received direct and indirect support during lean years, with Erbil reaching the AFC Cup final in 2012—a symbolic lift for a generation whose memories included sanctions, civil war, and displacement. The message was simple: civic pride can originate on a football pitch as readily as in a parliament chamber.

Cultural policy, likewise, tried to move beyond ceremony to access: funding streams for young artists, theater groups, and filmmakers; municipal venues that could be booked without prohibitive costs; and local media that covered culture as a beat, not a filler.

Civil society organizations multiplied after the 2011 NGO Law, working on the environment, women’s rights, humanitarian relief, and cultural production. The Region also became a refuge for journalists during the years when reporting in Baghdad was perilous.

By 2015, more than 2,500 NGOs were registered with the KRG, a steep rise from fewer than 300 a decade earlier.

A 2007 Journalism Law that prohibited imprisonment for publication offenses did not eliminate pressure on the media, and incidents of harassment and lawsuits persisted. But in comparative regional terms, the legal framework and relative security in Erbil and Al-Sulaymaniyah gave writers and editors more room than they had elsewhere in Iraq.

The civic map was not an accessory to the political project; it was one of its foundations, extending the idea that stability needed spaces where young people could belong, create, and be seen.

Women, Communities, and Pluralism by Design

One of the earliest signals of a widened political horizon was the appointment of a female minister in the KRG—initially exceptional, later part of an emerging pattern. A 30% parliamentary quota for women, support for girls’ schooling, micro-credit schemes for women-led businesses, and the creation of a Supreme Council for Women’s Affairs gave the inclusion agenda institutional backing.

By 2018, women held 111 out of 375 municipal council seats across the Region, a proportion higher than the Iraqi national average.

Progress was uneven and remains debated; nevertheless, the visibility of women in cabinet, parliament, and professional roles altered public life.

Pluralism was built into parliamentary allocation for communities too often described merely as “minorities”: Christians (Chaldeans, Syriacs, Assyrians), Yazidis, Turkmen, Armenians, and Feyli Kurds.

The Region reserved 11 parliamentary seats for these communities, and Erbil alone became home to more than 30 minority-language schools by 2014.

The Region’s response to the Yazidi genocide after ISIS’s 2014 onslaught included the establishment of an Office for Rescuing Kidnapped Yazidis, which coordinated with families and international actors to free and support survivors.

For the KRG, this was both a moral imperative and a statement about the Region’s identity. Nechirvan’s summary line captured it without ornament: “The Region will have no dignity unless every citizen, whatever their faith, ethnicity, or language, feels at home.”

The inclusion architecture did not erase grievances or resolve all representation disputes—particularly in mixed districts outside the core provinces—but it reshaped the Region’s internal map so that citizenship was not imagined as a single ethnic or religious profile.

Erbil’s External Turn: Consulates, Corridors, and Bridge Diplomacy

As the security situation in the rest of Iraq fluctuated after 2003, Nechirvan pushed an external strategy: make Erbil an accessible, predictable hub. He encouraged the opening of dozens of consulates and diplomatic missions, turning the city into a venue for UN, EU, and development conferences, and into a logistics base for NGOs and firms.

By 2019, Erbil hosted more than 35 foreign consulates and representative offices, second only to Baghdad in Iraq.

In practice, a foreign business traveler could land in Erbil, meet local partners and officials, and be in a bonded warehouse or factory the same day. That efficiency—rare in the region during those years—had outsized reputational effects.

Managing neighbors required different playbooks. With Turkiye, energy and trade formed the spine: the pipeline to Ceyhan, cross-border commerce, and a pragmatic dialogue with Ankara, even as the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) issue complicated security.

With Iran, familiarity bred during Nechirvan's youth and continued channels in Tehran prevented breakdowns and enabled coordination on border security and trade corridors.

In the Gulf, ties with the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia mixed investment with political signaling: red-carpet treatment in Abu Dhabi and the presence of Emirati companies in Erbil translated into third-party endorsements of the Region’s stability.

Western partnerships were built through steady, low-drama engagement. French presidents hosted him at the Élysée; US administrations across party lines received him in Washington and at global forums; and Pope Francis’s 2021 Mass in Erbil offered an image of pluralism that no press release could match.

The approach was less about headline agreements and more about a bank of trust—a ledger of kept appointments, predictable behavior, and punctual follow-through that made Erbil usable for others’ agendas. In turn, that usability became political capital for the KRG.

This outward-facing posture reinforced an inward message: Kurdistan’s cause would gain strength not only through battlefield history but through showing the world a functioning political and economic system—something that could be partnered with, invested in, and visited.

Baghdad, Budgets, and the Art of the Possible

The most consistent constraint on the KRG’s project has been fiscal dependence on the federal budget and the unresolved constitutional mechanics around oil and disputed territories.

Article 140 of Iraq’s 2005 constitution laid out a process—normalization, census, and referendum—to determine the status of disputed areas such as Kirkuk. The steps never reached their conclusion, leaving the question in limbo and inviting cyclical tensions.

Budget laws in Baghdad frequently conditioned or delayed transfers to the Region; in response, Erbil sought revenue autonomy through oil exports and local taxation. Each move sparked counter-moves: lawsuits in federal court, customs directives, and ad hoc bargains to unlock salaries.

For example, in 2019, the federal government froze transfers for three months, leaving nearly 1.3 million KRG public employees facing delayed salaries until a temporary deal was struck.

Nechirvan’s method in Baghdad earned him a reputation as “the open door”—a leader who would meet adversaries and critics, go personally to break deadlocks, and keep communication channels alive even during public escalation. That habit produced incremental gains rather than structural resolution: a tranche of salaries here, a memorandum there, a temporary framework for revenue-sharing that lasted a few months longer than expected.

For public employees in the Region, the technicalities mattered less than the outcome. Salary delays damaged trust and compressed household budgets for teachers, nurses, and municipal workers. Nechirvan acknowledged the hardship repeatedly and made salaries a stated priority, while pressing for predictable transfers from the federal treasury.

The combination of oil price cycles, federal politics, and geopolitics around export routes kept the problem recurrent. Yet his posture remained consistent with his core line about stability’s social foundations: “The stability we enjoy is the fruit of shared sacrifices, and Kurdistan will not be fully built unless we preserve and develop this stability together.”

2014 and After: Crisis as Stress Test

The ISIS offensive in 2014 was the Region’s stress test. Cities absorbed massive displacement; schools became shelters; hospitals and municipal services faced surges beyond their design. Oil prices fell; border trade slowed; federal transfers became uncertain.

At its peak in 2014-2015, the Kurdistan Region hosted nearly 1.8 million internally displaced persons and refugees, according to UNHCR—equivalent to almost one-third of its resident population.

The KRG’s response—imperfect and strained—relied on the earlier expansion of facilities and on external partnerships that Nechirvan had cultivated. UN agencies and NGOs used Erbil as a base; donor conferences found a venue; investment protections were renegotiated rather than entirely abandoned.

Domestically, the political center held but frayed. Public-sector arrears eroded trust; younger citizens, newly globalized through language and internet access, demanded more than stability—they wanted transparency, mobility, and opportunity outside government employment.

Those demands suggest the next phase of statecraft: diversification, labor-market reform, and a deeper rule-of-law consolidation that protects contracts and speech not only by custom or leadership personality but by institutions that outlast leaders.

Nechirvan’s posture during the crisis remained consistent with his long-held method: move quickly to convene adversaries; protect social services first; leverage external confidence to shore up internal gaps; and avoid escalations that can spin out of control.

He summarized the underlying logic in language that linked policy to social meaning: education, culture, and basic services are not ornaments of stability; “They are the architecture that keeps the ceiling from falling.”

Method and Mindset

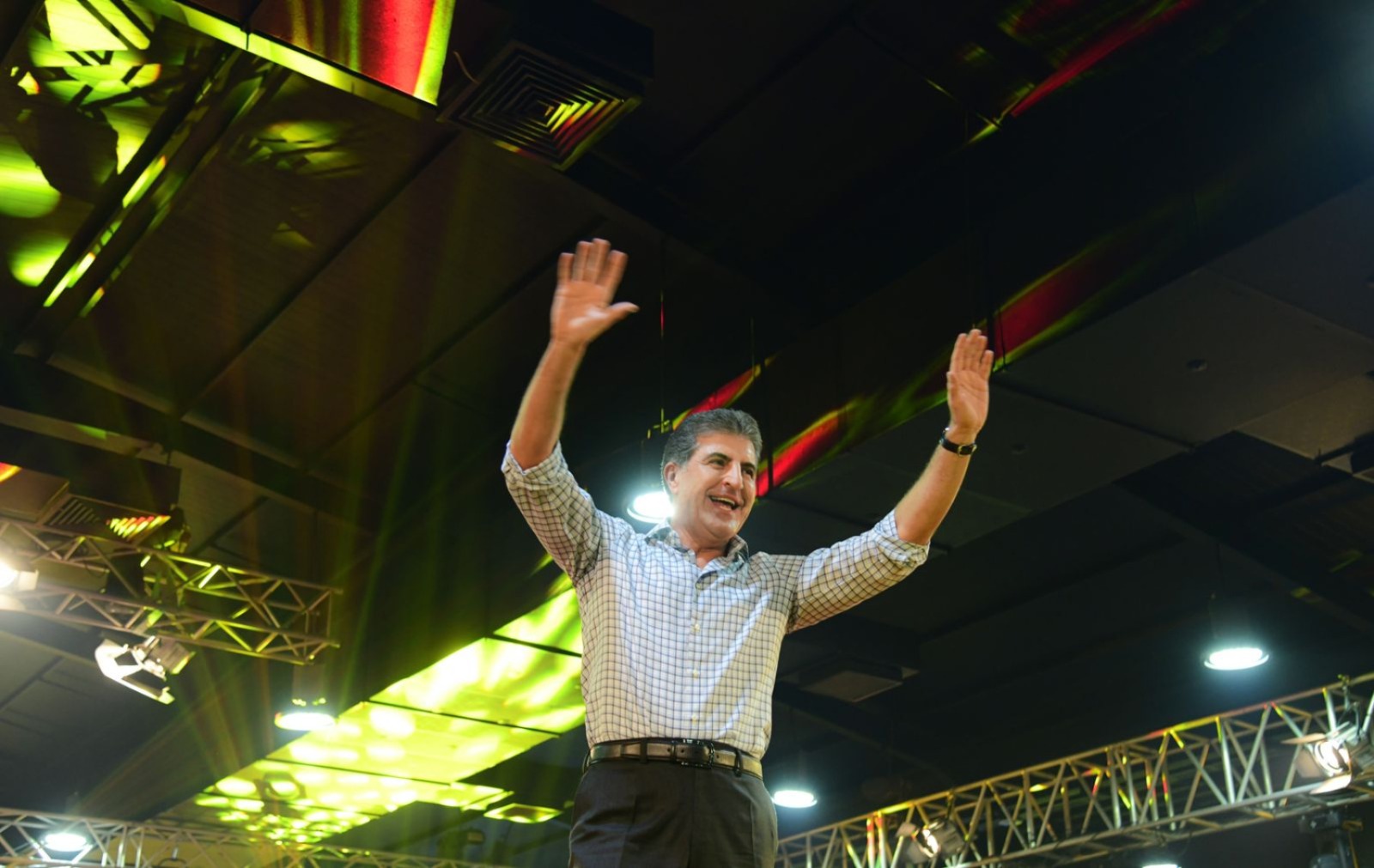

Nechirvan Barzani’s political method is neither ideological nor dramatic. It is procedural: put people at the same table who would rather avoid each other; define the minimum they can live with; and use the calendar—deadlines, budgets, visits—to turn that minimum into a decision. He relies on patience, repetition, and the idea that relationships are capital.

Such an approach may not always produce a decisive break with structural problems, but its advantage is that it reduces the frequency of disasters.

For readers beyond Iraq, the comparative regional context matters. In a Middle East where many sub-state authorities have either militarized governance or slid into factional paralysis, the KRG under Nechirvan’s watch tried to normalize: airports that function, consulates that issue visas, schools that open, and a recognizable bureaucracy that citizens can navigate.

The Region’s politics are still deeply competitive and sometimes abrasive, but the behavior of its institutions since 2003 is not accidental. It is, in part, the product of a political culture followed by Nechirvan Barzani that rewards tempering impulses and treating adversaries as future counterparts.

Next Tests for Leadership

Several files define the horizon of Nechirvan’s work:

-Revenue architecture: Even with legal disputes unresolved, the KRG needs diversified revenue beyond oil—industrial zones tied to regional supply chains, agribusiness modernized for export, and service sectors (health, higher education, logistics) that capture regional demand. The pipeline to Ceyhan was a milestone; resilience will come from multiple streams.

-Institutional distance: The next credibility gain lies in making ministries less sensitive to party rotation and more bound to rules—procurement standards, audits, and civil-service incentives that reward performance. Depoliticization is not a switch but a sequence of decisions that outlast any one cabinet.

-Federal compact: A durable Baghdad–Erbil understanding on budget transfers and energy—less tactical, more formulaic—would stabilize salaries and planning. That compact is political before it is technical, and depends as much on coalitions in Baghdad as on documents. Here, Nechirvan’s reputation as “the open door” remains an asset, but it will need to be paired with structural guarantees.

-Civic contract: Young Kurds will measure success not only by stability, but by mobility—the ability to start firms, move between universities and labor markets, and live under predictable regulations. Education’s gains will mean more if paired with growth sectors that can absorb talent and if the cost of participation—permits, utilities, financing—does not crowd them out.

None of these aims rests on one person. But Nechirvan’s roles—as KRG prime minister across multiple terms and, since 2019, as President of the Kurdistan Region—make him one of the few figures with the relationships and habits required to stitch together incremental progress. The same method that governed his earlier tenure—quiet persistence, external partnerships, and a bias for deal-making over grandstanding—will likely define his approach to the next round.

Legacy and Lessons

Profiles often over-credit individuals for collective work or over-blame them for structural constraints. A balanced accounting of Nechirvan Barzani avoids both traps. He did not build Kurdistan’s institutions alone, but he was central to how they were built: gradually, through inclusion, and by turning external credibility into internal room to maneuver.

He did not solve the Region’s deepest problems, but he helped prevent their worst outcomes. His style lacks theatricality: its register is administrative.

In a landscape accustomed to loud claims, that quiet register is easily missed. Yet it is visible in the daily routines that define statehood. The “golden decade” was neither myth nor miracle; it was a period in which incremental governance created a platform that, while tested, did not fully crack when the storm came.

There is unfinished business, but the record shows a leader who approached politics as craftsmanship, not spectacle—more conductor than soloist, more architect than orator.

In Kurdistan’s evolving story, that combination—competence, patience, and negotiated confidence—is its own kind of power. And it rests on a principle he voiced in the language of both aspiration and restraint: “The building of our homeland will only be complete when hearts and positions come together.”

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.