Shafaq News

Through the winding alleys of Kirkuk Citadel, where centuries of dust and history linger in the air, a green dome rises above the old quarter. Known locally as the Baghdadi Khatun Dome, the monument weaves together legend, faith, and craftsmanship, standing as both a relic of Islamic art and a testament to the city’s rich and layered identity.

The Green Dome ranks among the oldest landmarks within the citadel. It dates back to the 14th century, specifically 762 AH/1361 AD, during the Jalayirid dynasty, which ruled Iraq and western Iran from Baghdad after the fall of the Mongol Ilkhanate — a period marked by a blend of Persian, Turkish, and Mongol artistic traditions and a revival of Islamic architecture.

Historical records suggest that the shrine was built to honor Baghdadi Khatun, a young woman who died in Kirkuk during a pilgrimage to Mecca. Her father, a prominent figure of his time, commissioned the shrine to preserve her memory. Some historians, however, believe the name may symbolically refer to Baghdad itself, reflecting the capital’s political and cultural prominence during that era.

Stone Survives

From the exterior, the Green Dome takes an octagonal form, symbolizing the transition from the square of earth to the circle of heaven — a motif deeply rooted in Islamic geometric design. Its façade was once covered with Qashani, a square-shaped ceramic tile, in gradients of turquoise, cobalt blue, and green, earning the shrine its enduring nickname: the Green Dome.

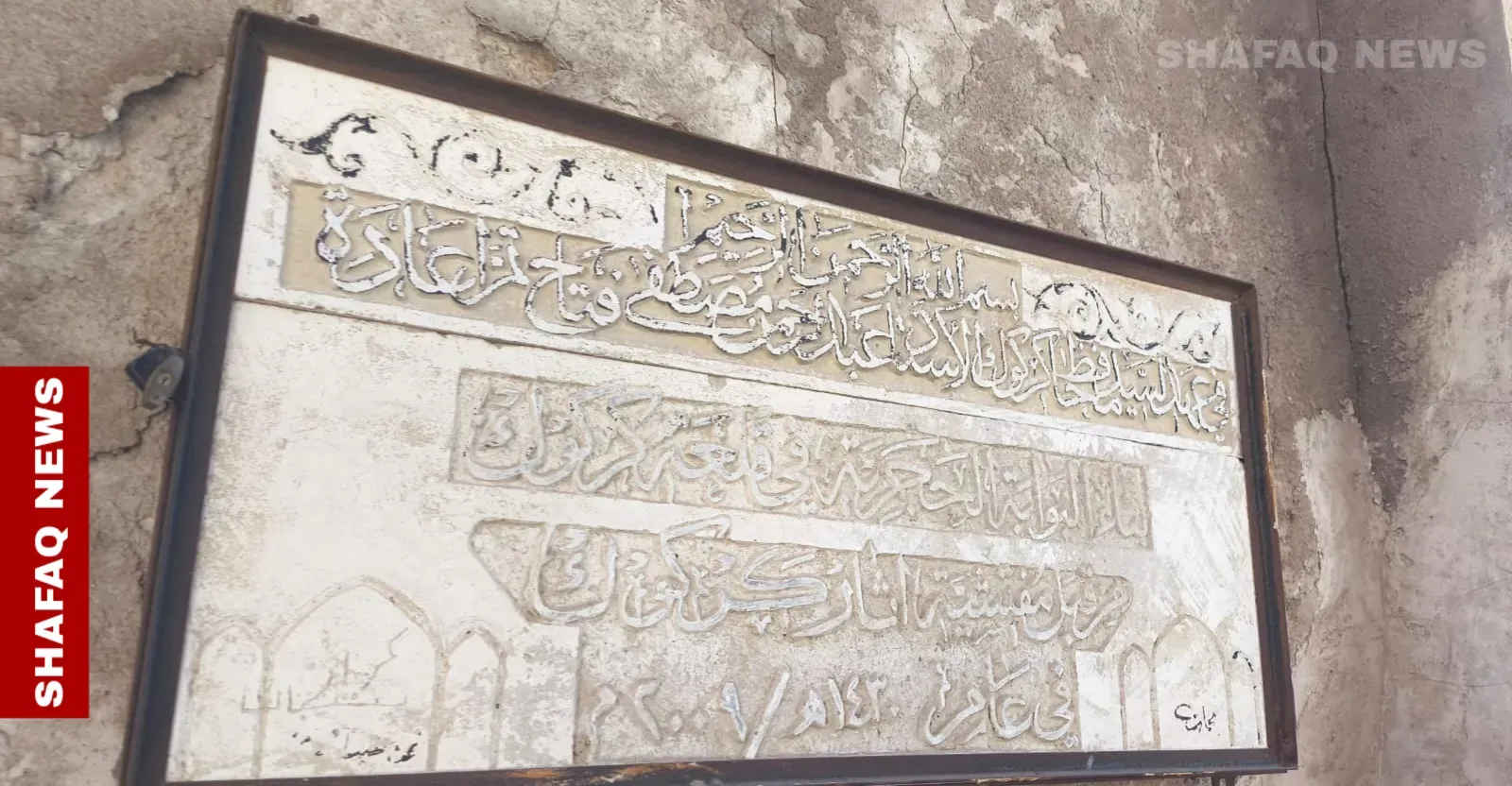

Inside, the shrine reveals a chamber embellished with geometric patterns and Kufic inscriptions that reflect the precision and artistry of 14th-century craftsmen. Archaeologists document that the interior walls were once enriched with intricate stucco reliefs, merging Central Asian motifs with Mesopotamian traditions to create a distinctive aesthetic.

“The design reflects a fusion of Mongol and Persian influences,” explained Saad al-Din Mohammed, a restoration engineer specializing in Kirkuk’s heritage. “Its decorations resemble those in the shrines of Tabriz and Samarkand, with distinctive local touches using Kirkuk’s traditional clay and gypsum.”

Mohammed noted that the structure comprises two levels: an underground crypt believed to contain family burials, and an upper chamber housing the main tomb. “The outer dome was once covered with glazed tiles, most of which have deteriorated over time due to exposure and neglect,” he remarked.

Experts estimate the dome once stood about 10 meters high, with an internal diameter of nearly six meters, giving it a compact yet commanding presence over the citadel. The tilework, likely produced in workshops in Baghdad or Tabriz, links the monument to other Jalayirid-era landmarks, including the Tomb of Sheikh Safi al-Din in Ardabil and the Soltaniyeh Dome in Iran.

Neglect Threatens Memory

Despite its historic and architectural significance, the Green Dome now bears visible cracks and erosion. Its once-glazed tiles have faded, and sections of the façade have fallen away under centuries of exposure and neglect. The surrounding citadel is dominated by deteriorating buildings, and parts of the site remain closed due to safety concerns.

“We used to visit it during the holidays to recite prayers,” recalled Jabar Qadir, a longtime resident. “It was a place we loved since childhood. Now it stands abandoned — the blue tiles that once sparkled in the sun have mostly fallen off.”

A restoration effort launched by the Kirkuk Directorate of Antiquities in 2018 was halted within months amid funding shortages and administrative shifts. After that short-lived attempt, the directorate began preparing a comprehensive new restoration plan under international supervision.

Officials indicate that the directorate receives less than 10% of the annual budget required to preserve Kirkuk’s heritage, which includes more than 250 registered sites.

Today, over 80% of the citadel’s buildings are in varying states of disrepair.

Broader challenges have further strained preservation efforts. Iraq counts six UNESCO World Heritage sites in various parts of the country — including Hatra, Samarra, Erbil Citadel, and Babylon — yet Kirkuk’s citadel remains at the nomination stage, hindered by incomplete documentation, structural vulnerabilities, and administrative obstacles that continue to delay progress.

“The dome is a central feature of Kirkuk’s nomination file,” highlighted Raed Akla, Director of Kirkuk Antiquities and Heritage, noting that the directorate is preparing a new comprehensive restoration plan under international supervision.

He also emphasized that the program would employ laser-based documentation, 3D mapping, and moisture stabilization, following techniques successfully applied at the Erbil Citadel, warning that any unplanned restoration could threaten the monument’s authenticity.

Shared Devotion

Beyond its architectural value, the Green Dome carries layers of legend and faith. The story of Baghdadi Khatun has long been interwoven with Kirkuk’s collective memory — a tale of devotion and loss that continues to endure through generations.

“Her story reflects love and fidelity,” remarked Muthanna Abdulqadir, a heritage researcher. “Her father’s grief transformed into an enduring monument — a story of parenthood and longing that still lives in the city’s folklore.”

Over time, the shrine became a shared spiritual refuge for Kirkuk’s diverse communities. “People from different religions once visited the dome for blessings and prayers — Muslims, Christians, even Jewish families before the mid-20th century,” Abdulqadir noted, emphasizing that it stood as a rare expression of unity and reflected the city’s inclusive character.

Residents recall how visitors would light candles, tie ribbons to the iron gate, or leave offerings of flowers and sweets — simple gestures of devotion blending Islamic and folk traditions. During festivals, particularly Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, the shrine served as a gathering point for collective remembrance.

Before partial closures, the citadel attracted thousands of annual visitors, mostly domestic tourists and school groups. Preservation advocates believe that restoring the site could help revive cultural tourism and create jobs for local artisans and heritage experts.

Despite its scars, the Green Dome remains a reflection of the city’s enduring soul — a quiet survivor of time, memory, and devotion.

Written and edited by Shafaq News staff.